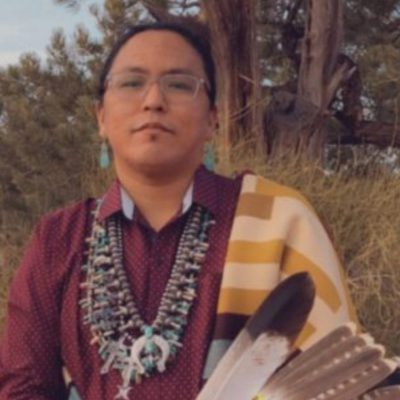

Mygk! Hello, my name is Michael King. I’m 32 years old and come from a small community called Navajo Mountain, about five miles from the Utah/Arizona border. It is called Kaivayaxaru, “The Mountain Place.” I’ve lived here my whole life, only leaving for school. I come from two different tribes. I am Navajo on my mother’s side and San Juan Southern Paiute on my dad’s side, and I am enrolled with my dad’s tribe.

We are a small tribe of about 300 members, and we’ve been federally recognized as a sovereign nation just since the 1980s. We had lost recognition during the Termination Era in 1933, when our homeland officially became part of the Navajo Nation. We were declared terminated by Congress. The federal government saw us as too intermarried with the neighboring tribes—Navajo, Hopi, and Ute tribes—and assumed we were no longer a distinct nation.

We are a nation. Despite our culture changing and evolving, we kept our unique identity throughout the assimilation with the greater American society and with the culture of our neighboring tribes. We picked up the language, the culture, and the spirituality of neighboring tribes. That’s the reason I am both Paiute and Navajo, and I am multilingual. I can speak Navajo fluently, but when we are at home, we speak and hear our Paiute language. Our unique culture still lives in our home. When we leave our door, we switch back to Navajo because that’s the greater society. And when we leave Navajo, we switch to English. That was a really big cornerstone of our survival—to adapt not just the American culture, but the greater neighboring tribal culture of the Navajo and Hopi, but we’ve remained true to our tribal identity.

I ran on a campaign of upholding our sovereignty. What I mean by upholding our sovereignty is asserting that we’re still here. A lot of people, even in my own community, believe that we are no longer here. They say that their grandparents told them that we no longer exist. We’re very much here. I want to uphold our sovereignty, and part of that is being recognized by our neighboring tribes and by the regional and municipal leaders around us.

Another part of upholding our sovereignty is the establishment of a homeland. I anticipate creating dialogues with state, tribal, and federal governments about securing land. Without land, we can’t really build infrastructure. Without infrastructure, we cannot have services of any kind. So right now, my main priority to my tribe is securing our previous territories and our water rights, as well.

Having a place to call home is a big part of our identity. Even though we do have a home here—we live here—the legalities and logistics mean we have no access to land. This is considered Navajo land, held in trust for the Navajo by the federal government. Being San Juan Southern Paiute, I have no capacity to build a home. That’s not to say I physically cannot. It’s the bureaucracy, laws, and policy that make it impossible. My mother is enrolled with the Navajo Nation, so she has a right to build a house and live here. That is the reason why I live with my parents. My father is San Juan Southern Paiute, so he can only live here because he is married to my mom.

Our ancestors are here—their old homes, their burials, their cornfields, old shrines, they’re all still here. When you look back on history, my ancestors helped the local Navajo people here. But to this day, we are bullied with legislation and policy, making it harder for us to go to school, get a home, receive healthcare from Indian Health Services, or even get jobs. So, land is a really big part of our identity, not just in a romantic sense, but legally and logistically. We need land in order to continue to be who we are as Paiute people and to secure a future.

I believe I can help to make this change. From a very young age, I knew I was different. My family knew I was different, but they never put a label on it. As Native people, we try not to label anything as concrete, as absolute, especially concerning Two Spirit people. There’s not an absolute term or idea concerning our gender roles and relationships within our society. In Navajo and Paiute, the word for Two Spirit people is nadlééh and Tuuwasawudts’. Nadlééh is a word meaning “constantly changing or evolving” and Tuuwasawudts, “dressing like the other sex,” is a more recent term. There is another Paiute term which refers to one person holding both the basket and bow—an old metaphor to refer to the role and identity of both a male and female essence in what we call gender identity.

Hunting is part of our culture; we hunt deer and elk. That’s part of our sustenance for the winter. When I was twelve, I told my family that I can no longer go to hunt. I couldn’t explain it at the time and I didn’t know why, but my grandparents knew—they understood. It took another ten years before I knew why. There have been others in my family, and there were previous Two Spirit members in our communities. It’s very taboo in recent history because our culture today became very conservative and Christian to survive within the greater culture. But in the back of their minds, our people still remember those old teachings. That was the thing that my parents and grandparents knew. I took on the roles of both male and female within my own home. I’m actually the oldest child and oldest grandchild in my family. That meant helping my parents and grandparents. Sometimes I would do the typical male roles, and sometimes female ones. That was just normal for me. It was normal in the survival of us as Paiute. Everyone helped in all roles. It was fluid. The social construct of gender wasn’t definite as it is in Western ideologies.

I was always told Two Spirt people make good leaders because we have a sense of two perspectives, sometimes three. We see all aspects of the situation. Where most people are quick to make a decision, I take my time. I think, “How would the men folk see this?” “How would the women folk see it?” The inner conflicts between people in many of our Creation stories were resolved by Two Spirit people. I feel we need to take back our role in our communities.

Growing up Two Spirit in a very small, remote community, I never thought this would be possible. I never had role models or leaders to look up to. That’s another reason why I decided to become niavipaxai’ni, a leader. I want my nieces and nephews to look back and say, “Uncle was a leader, and he was Two Spirit. He was able to help the people. Maybe other Two Spirit tribal members will think, “He did it, and he’s like me.”

As Two Spirit people, we were the leaders, the healers, the matchmakers, the warriors as well as the peacekeepers. We were in every aspect of tribal society. These were our roles. And we were respected and revered. I want to show that even to this day, we can continue to fulfill those roles. Even if just one Indigenous youth, one Two Spirit youth out there sees this, I hope I can be that inspiration to them that I wish I had when I was younger.

It all starts with you. Anything you want to do, you’re able to do. What we say in our language is “weenuuhg,” meaning “stand up”—Anything you want to do, it starts with you. If you want to do something, put your mind to it and go for it. There may be some doubt and there may be people who will want to stop you, but if it’s something you believe in, go for it. That’s part of our teachings, not just as a Paiute person, but as an Indigenous person. It starts with you.